With the fast pace of urbanization, especially in metro cities, the issue of sustainable management and disposal of Municipal solid waste (MSW) deserves the attention of all stakeholders of society. This can be achieved by following the globally established business rules of MSW management. In this paper Dr. Anil Kumar Agnihotri discusses how MSW is a serious issue in India needing immediate attention for managing it sustainably and for making Bharat Swachh and healthy.

In India, policy planners have never considered waste management in general—and municipal solid waste (MSW) management in particular—to be a part of development and urbanization process. landing us in the present crisis of MSW management.

The Swachh Bharat Mission launched by the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India in 2014 is a silver lining in this regard. Recently, an important announcement regarding the Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 was made by the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India on 1st October 2021, in which he said that the aim of this phase was to make our cities garbage-free. The second phase of Swachh Bharat aims at sewage and safety management: making our cities water-secure and ensuring that dirty nallahs (sewers) don’t merge into rivers. This needs immediate attention of the top policymakers to bring out an explicit policy-based programme backed by sound policy regime and political will. Until 2000, we did not even have any law specifically on how to deal with MSW. Environment related legislation, such as Water (Prevention & Control of Pollution) Act, 1974; Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981; and Environment Protection Act, 1986; was introduced but, the subject of MSW was largely neglected legislatively. Certain rules like Hazardous Wastes (Management and Handling) Rules, 1989 and Biomedical Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 1998 dealt with the subject only tangentially. This glaring oversight was compounded by the cash-strapped status and general indifference of the civic bodies towards maintaining a functional MSW disposal system.

Recently, the collection of MSW has significantly improved, but there are still issues in its final disposal. The reason behind this is that the technology being used is not suitable for Indian garbage. This is because the inherent calorific content of MSW is not sufficient for its incineration. Besides, incineration is an unsafe method of disposal. The other issue is that utility companies handling the disposal of MSW are not honouring the prevailing MSW Rules.

Municipal Solid Wastes (Management and Handling) Rules, 2000

MSW Rules, 2000, were applicable on ‘every municipal authority responsible for the collection, segregation, storage, transportation, processing, and disposal of municipal solid wastes’. It fixed certain responsibilities for monitoring and ensuring eco-friendly compliance and submitting Annual Reports on municipal authorities, State Governments and UT Administrations, as well as Central Pollution Control Board and the State Board; or the Committees in infrastructure development that were setting up landfills and other waste processing and disposal facilities.

Current Status

With the ever-increasing population and urbanization in India, waste management has become a major challenge, especially in the urban setup. Over the years, there has been a stark increase in the quantity of waste generated and it is only expected to increase further in the coming years. The characteristics of waste being disposed have also undergone a transformation, especially with the increased use of electronic gadgets and equipment.

Currently, as per government estimates, about 65 million tons of waste is generated annually in India, and over 62 million tons of it is MSW (organic waste, recyclables like paper, plastic, wood, glass, etc.). Only about 75-80% of the municipal waste gets collected; out of this only 22-28% is processed and treated. The remaining MSW is deposited at dump yards. By 2031, MSW generation is projected to increase to 165 million ton, and further up to 436 million ton by 2050. The waste collection efficiency needs to catch up with the increasing quantity of waste generated in India. It ranges from 70 to 90% in major metro cities and is below 50% in many smaller cities as of now.

Issues regarding management of MSW:

The ‘Position Paper on MSW’ (2009) of the Government of India raises important issues regarding the management of MSW.

- There are serious barriers to private sector participation in urban infrastructure as the financial status of ULBs, except for a minority, is precarious. Urban sector is seen as a high-risk sector also because of institutional complexity, due to the multiplicity of agencies involved in service delivery.

-

Further, there is lack of regulatory or policy enabling framework for PPPs (Public-Private Partnership), barring a few exceptions, along with a lack of bankable and financially sustainable projects, considering the opportunities and risks involved.

-

Lack of commitment by municipal authorities to ensure compliance of source segregation of MSW. This is an important for safe disposal of MSW and for successfully structuring its treatment on a PPP model. Achieving this will ensure proper treatment of MSW and success of PPP.

Apart from the aforementioned problems, the most important issue regarding MSW management is that these projects should be planned on the basis of negative pricing. A negative pricing/ externality occurs when an individual or firm making a choice does not have to pay the full cost of the choice. If any good has a negative externality, then the cost to the society is greater than the actual cost paid by the consumer. A common example of a negative externality is pollution. For example, a polluting industry might pump pollutants into the air. While the industry has to pay for electricity, materials, etc., the individuals living around the industry will pay for the pollution at the cost of their well-being, because it will affect them adversely. They would have higher medical expenses, poorer quality of life, reduced aesthetic appeal of the air and so on—a cost that the industry does not pay.

However, when disposed at proper the dump site, MSW is a state asset. Hence, this is the sole responsibility of the state to collect and dispose it of in a scientific and sustainable manner.

On the bright side, MSW Rules, 2016 have just come into effect and contain beneficial provisions, like:

- Dairy waste, which is major polluter of rivers, has been covered under the said legislation.

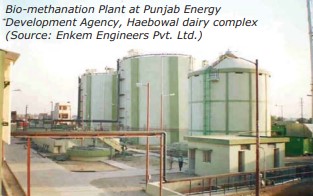

- For the first time, bio-methanation has been emphasized for treatment of segregated organic part of MSW – because the waste generated in our country is high in organic content, with high moisture and low calorific content. Bio-methanation is a proven technology that can treat freshly segregated organic fractions of MSW, and hence, there is no need to dump the entire garbage in landfills. Only the non-organic matter will go to landfill and even this can be recycled by further segregation to paper, plastics, glass, etc.

Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016

- A major overhaul of environmental policies was introduced in the 2000 Rules. The scope of application of MSW rules has been expanded by including under its ambit: places of pilgrimage, airports, special economic zones, ports and harbours, defence establishments and every domestic, institutional, commercial and any other non-residential solid waste generator.

- These Rules, for the first time, prescribe the duty of a MSW generator. A Central Monitoring Committee is to be constituted for monitoring implementation. Criteria for land filling and waste-to-energy plants are also provided.

- Moreover, the Rules moreover prescribe the duties of Ministries and Departments other than Ministry of Environment & Forests. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (Ministry of Urban Development in the Rules) will issue technical guidelines and the National Policy on MSW; in addition to providing training and financing as well as promoting R&D.

-

Departments of Fertilizers & Chemicals (presently divided between the Department of Chemicals and Petrochemicals and the Department of Fertilisers; also put under the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers) will aid market development for city compost. The Ministry of Agriculture will propagate utilization of compost on farm land. Whereas, the Ministry of Power will have to compulsorily purchase power generated from waste-to-energy plants.

- Central Pollution Control Board will have to coordinate with the State Pollution Control Boards, review environmental standards, monitor implementation, publish guidelines and prepare an annual report on implementation.

- Duties are also assigned to Secretary–in-charge of Urban Development in the States and Union territories, District Magistrate, Village Panchayats and manufacturers or brand owners of disposable products, sanitary napkins and diapers.

Technologies are available for managing MSW of all sorts of composition. Pertinent to mention at this juncture that we have to revisit the practice we have followed so far, in the so called waste-to energy plants. These plants at Hyderabad and New Delhi, flagrantly violate the MSW Rules, 2016.

As per a paper published by the Global Anti-Incinerator Alliance & Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives in 2003 the problems of waste incineration are:

“pollutant releases, both to air other media; economic costs and employment costs; energy loss; un-sustainability and incompatibility with other waste management systems. It also deals with problems specific to Southern countries.”

The paper, titled “Waste Incineration: A Dying Technology”, goes on about “Dioxins” which “are the most notorious pollutant associated with incinerators”. Along with causing a wide range of health problems (cancer, immune system damage, reproductive and developmental problems) Dioxins also bio magnify, meaning they are passed up the food chain from prey to predator.

The author of this paper, Neil Tangri, points to incinerators as the primary source of dioxins worldwide. He also points to incinerators as a major source of mercury pollution and of other heavy metal pollutants such as lead, cadmium, arsenic, and chromium. Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin, impairing motor, sensory and cognitive functions.

Other concerning pollutants include other (non-dioxin) halogenated Hydrocarbons; acid gases (precursors of acid rain); particulates which impair lung function; and greenhouse gases. Even with these, the characterization of incinerator pollutant releases is still incomplete; there are many unidentified compounds present in air emissions and ashes.

The paper continues to showcase how:

“Incinerator operators often claim that air emissions are “under control,” but evidence indicates that this is not the case. First, for many pollutants, such as dioxins, any additional emissions are unacceptable. Second, emissions monitoring is uneven and deeply flawed, so even current emission levels are not truly known. Third, the data that do exist indicate that incinerators are incapable of meeting even the current regulatory standards.”

With incinerators being unsustainable and obsolete, innovative practices for sustainably managing waste are being adopted around the world. In our country, during the last few years, a number of incinerators have been put up which are of a primitive type without proper emission control arrangements; these plants are flagrantly violating environmental norms as per MSW Rules, 2016.

As per the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 (as amended) under section 21: Criteria for waste to energy process –

1. Non recyclable waste having calorific value of 1500 K cal /kg or more shall not be disposed of on landfills and shall only be utilised for generating energy either or through refuse derived fuel or by giving away as feed stock for preparing refuse derived fuel.

2. High calorific wastes shall be used for co-processing in cement or thermal power plants.

3. The local body or an operator of facility or an agency designated by them proposing to set up waste to energy plant of more than five tons per day processing capacity shall submit an application in Form-I to the State Pollution Control Board or Pollution Control Committee, as the case may be, for authorisation.

4. The State Pollution Control Board or Pollution Control Committee, on receiving such application for setting up waste to energy facility, shall examine the same and grant permission within sixty days

Suggestions:

1. For MSW management and disposal projects, economic evaluation should be done on negative pricing mode.

2. We should not forget that the garbage produced in our country has a very different composition as compared to developed nations; Indian garbage is high in organics and moisture content and has very low calorific contents while the garbage from developed countries has reverse values, therefore, the prevailing technologies for MSW management in the developed world cannot be justified to be applicable in India.

3. Looking at the hazards involved in this sector and with the burgeoning population and stress on per capita availability of urban space, finding finances should not be an issue. In India there are a number of subsidized services, such as, postal, water, energy, transportation, food and health, etc., therefore, subsidy could be given in MSW sector as well. In addition, if we conduct a proper economic analysis of the industry, the payback will be very fast with the added advantage of India being on the path of becoming a healthier and cleaner nation.

4. The fiscal aspect of this sector is a very vital issue. These projects need huge investments and regular operations (utility, etc.) require capital expenses; if such incentives are provided to operators, these projects are bound to run successfully.

The salient suggestions/recommendations of the Position Paper, 2009 of Government of India are:

Given the lack of in-house capabilities of municipal authorities and paucity of resources, it is desirable to outsource certain services and resort to PPP/NGO participation in providing Solid Waste Management services. The private sector has been involved in door-to door collection of solid waste, street sweeping (in a limited way), secondary storage and transportation, and for treatment and disposal of waste.

Municipal Corporations and city governments create and maintain assets with funds provided by Central and State grants, funds internally generated by local governments through taxes and tariffs, capital markets, etc. The Central Government should take up the role of a regulator by addressing the financial sector and related regulatory issues.

State Governments should also respond by enacting Model Municipal Laws to enable PPPs, setting up regulatory authorities and creating cadre of professionals at ULBs and state level.

Thus, it is imperative that while framing the policy the mind-set of the people at large is kept in view. This sector should be run in the public–private partnership (PPP) mode only, and there should be bare minimum intervention from government agencies – except identification of the right entrepreneurs for waste collection and of utility operators to dispose the MSW in the most scientifically without affecting the ecosystem.

The Way Forward

Dr. Anil Kumar Agnihotri is a Waste management Consultant at The Energy and Resources Institute and also contributes as an Energy Efficiency expert at Solutions for Clean and Healthy Environment foundation.

- Ensuring financial commitment based on the present data on MSW

- Opening this sector to private sector with strict compliance of MSW Rules, 2016. Inviting an expression of interest by the respective agencies for MSW collection and its scientific disposal, keeping in mind the concept of negative pricing – which is prevalent all over the world in such projects – and ensuring that it conforms to the prevalent statutory standards.

- Developing various concessional agreements pertaining to such projects with implicit roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder, along with relevant administrative mechanisms to ensure effective implementation of these agreements with clear provisions for administrative accountability.

- Provisioning for performance guarantee and strict monitoring of these projects; right from construction to implementation.

- Provisioning for stakeholder participation and encouraging them to visit to ensure that due care of the environment is taken by the project executor.

- Giving importance to decentralised, integrated MSW facilities where-in the MSW components should be segregated, i.e., construction and demolition waste, road side dust, biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste, because segregation of MSW at source has not been successful so far.

- Biomethanation may be preferred option for ultimate sustainable disposal of MSW, because Indian MSW is very rich in organic content and moisture content along with low calorific content. The remaining inert and recyclables can be gainfully utilised.

This article and more from TerraGreen can be viewed here: https://terragreen.teriin.org/